The Haunted House in Film

The energy of spaces and the shadow in the basement.

Somehow it’s October already. Which (at least to me) means it’s time for leaf-peeping, celebrating the thinning of the veil between the corporeal and spiritual worlds, and watching a shitload of scary movies.

In honor of the season of the witch, this month I’ll be writing about all things horror. Today I’m kicking it off with one trope I’ve been thinking a lot about lately — the haunted house.

I’m currently cleaning out the house I grew up in. And while I wouldn’t say this house is haunted, there’s definitely a lot of emotional energy tied up in here. The house feels like a living being, or at least like it contains a piece of me and every member of my family who’s lived here.

All spaces hold energy. Even if you consider yourself a rationalist, I’d be willing to bet that at one time or another, you’ve walked into a place and thought “this feels warm and inviting” or “the vibe is off in here.” Or perhaps you spent a weekend spring cleaning, and afterwards your home felt like it took on a bright new life.

That’s the energy of the space speaking to you.

So how is this energy represented in horror films?

Haunted Houses and the Architecture of the Psyche

When we look at the trope of the haunted house in film, we can consider the house as metaphor for the psyche.

You are the house, and the house is you.

From a Jungian perspective, the first floor represents conscious awareness, the rooms where daily life plays out. These are the public facing rooms, the ones we allow everyone access to. Bedrooms are more intimate — they symbolize our private thoughts, the parts of the psyche we keep reserved for ourselves and those closest to us.

We can understand the basement, then, to represent the deep unconscious —the shadow realm. Basements terrify us because they contain everything we’ve repressed — primal desires, grief, our collective fears.

This is why so many haunted house films stage their most frightening scenes in basements.

In the original The Amityville Horror (1979), George and Kathy Lutz get a great deal on a house in upstate New York because a young man named Ronald DeFeo had murdered his entire family in it a few years earlier. (I would never buy a house like that, but you do you I guess.)

Turns out the house is haunted.

After experiencing a series of paranormal events, the Lutzes discover a secret room in their basement that had been walled shut — a literalized portal to hell, constructed many years ago by a known Satanist who once lived there.

What’s concealed in there, in the unconscious, eventually must come out.

In the film’s climax, the walls bleed and a black primordial ooze fills the basement. George falls into this sludge pit but is able to escape — unlike the Ronald before him, George has faced his own shadow and integrated it — and the Lutzes flee the house, leaving all of their things behind.

This model—trauma made spatial—runs through nearly every classic haunted house narrative.

In Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963), Eleanor, a lonely, repressed woman, arrives at Hill House for a paranormal study. It’s clear that she’s attracted to Theo, another woman who’s there for the study, but Eleanor won’t allow herself to embrace her desire.

The haunting occurs when Eleanor’s sublimated emotions and repressed sexuality begin to bubble up through the psychic realm and manifest in the physical as uncanny disturbances: pounding doors, groaning walls, whispered voices.

As her desires move closer towards conscious expression, the walls of the house undulate and threaten to burst. The haunting is Eleanor’s repression externalized; Hill House becomes a projection of her psyche, its violence a reflection of her inner turmoil.

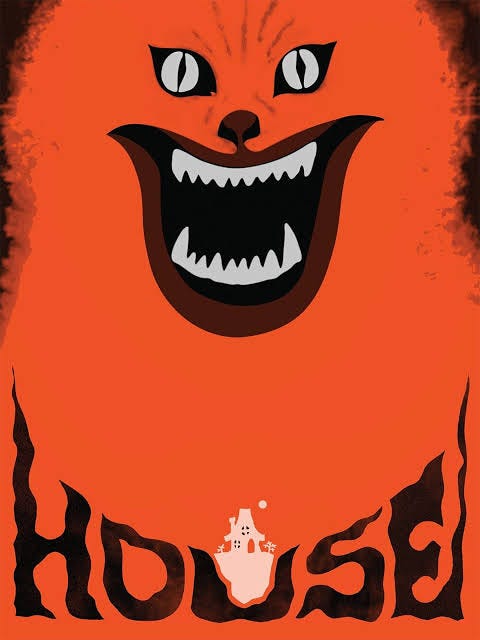

Where The Haunting suggests the house as projection, Nobuhiko Ôbayashi’s epically strange House (1977) takes it one step further. The house is not occupied by an energy that haunts it, but the house itself has become the haunting.

The film follows Gorgeous, a teenager who brings six friends to her aunt’s isolated country home. But this is no ordinary domestic space. The house is alive, ravenous for the essence of youth, and overflowing with the aunt’s grief.

Many years ago, the aunt’s fiancé was drafted into the war, and they made a promise to wait for each other. But he died in battle and she never left — instead, she’s merged with the house. She speaks to the appliances like they’re alive, saying things like, “the young woman will warm you, dear stove.”

The house feeds on the girls, literally — a piano eats one, a mattress consumes another — and redistributes their energy back into the aunt, who becomes younger and healthier until she’s able to take over Gorgeous’s body altogether and finally leave, trapping Gorgeous inside to continue the cycle of living as the house. The haunted house is no longer a structure containing trauma but a living archive of it.

Unlike The Haunting, where the house is a mirror of repression, Ôbayashi presents the house as a site of intergenerational trauma. The aunt’s wartime loss—the death of her fiancé and the subsequent erasure of her place in the social order—mutates into an architecture that consumes the next generation. Trauma becomes not just inherited but embodied in space itself.

This tradition continues into contemporary horror. In Remi Weekes’s His House (2020), the haunted house becomes a site of displacement trauma.

A South Sudanese couple seeking asylum in England are given a dilapidated government house, but what haunts them is not the peeling wallpaper or flickering lights—it’s the trauma they carry with them. A spirit, the apeth or “night witch,” crosses the ocean with them, a manifestation of guilt, loss, and the violence they endured in order to survive. The film literalizes the impossibility of starting over without confronting the past: to repress trauma is to invite it to infest the home.

So then, to enter a haunted house is to confront the ghosts we all carry within us.

The house is never just a house. You are the house, and the house is you.

Until next time,

Tara